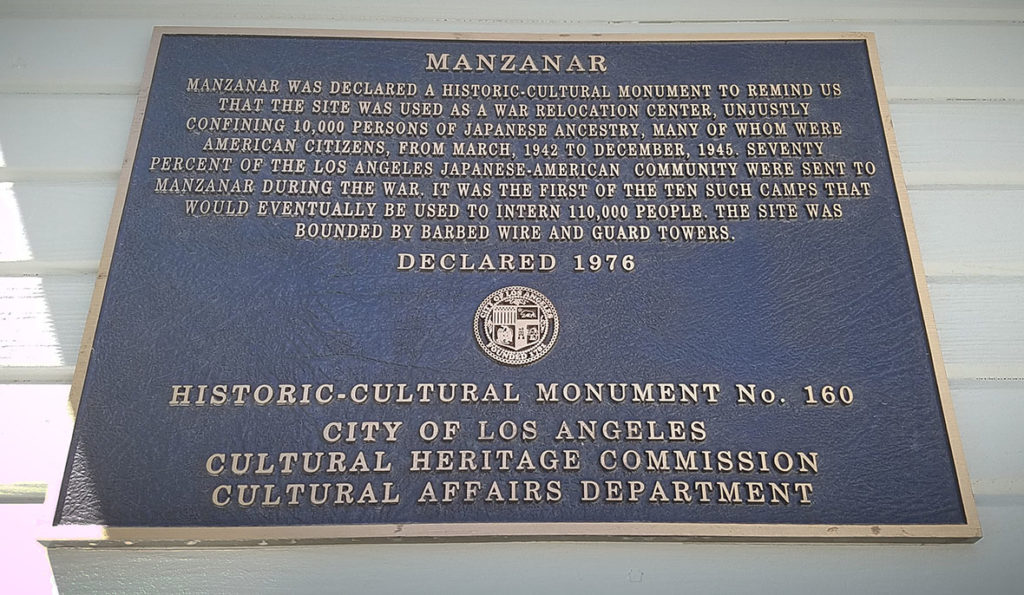

Japanese Internment Camp – Manzanar

It’s not the type of place one visits to pose in front of a monument or artifact, donning a big smile. It’s not the type of place one visits with a sense of excitement, like Disneyland or the world’s largest yarn ball. There’s nothing to smile or laugh about in the presence of Manzanar, a Japanese internment camp where over 10,000 men, women, and children of Japanese descent were imprisoned in 1942 following the bombing of Pearl Harbor.

Executive order 9066, signed by Franklin D. Roosevelt on Feb. 19, 1942, ordered all persons of Japanese ancestry, as well as some Italians and Germans, to relocate to one of ten internment camps throughout the United States. They were falsely told the “relocation” was for their own safety. American and immigrant citizens alike were met with harsh conditions simply because of their ancestry. In 1945, the order was rescinded, shutting down all of the camps with no prisoner accused of a single crime.

FEAR BEGETS FEAR

I visited Manzanar this past weekend. The historical site off US highway 395 was once the grisly setting where men were shot for gathering scrap wood to build their family furniture, where human beings lay in bed at night staring up at the night sky because there were holes in their roofs, and where thousands of people were held captive because of fear. Does this sound familiar – fear of a specific group of people because of an isolated incident? I couldn’t help but think if we were not careful, history could repeat itself.

I highly recommend checking out downtown Los Angeles’s Japanese American National Museum’s exhibit, Instructions to all Persons: Reflections on Executive Order 9066. It runs until August 13th, 2017. I learned much of the history from the museum. However, actually standing in the very place where such horror and injustice occurred was sobering, to say the very least.

I was standing in one of the barracks, reading and looking at the makeshift rooms that provided a visual for the conditions in which large families lived. Some of the single men and women shared rooms with several other single men and women, having to hang sheets as room dividers.

On the other side of the thin walls, I could hear two men conversating. One of them casually stated, “This isn’t so bad.” He was speaking in reference to the size and condition of the room in which he was standing. I couldn’t help but roll my eyes, scoffing in disgust at the white privilege he was so blindingly exhibiting.

They made their way into the room I was in. The same guy who made the ignorant statement proceeded to press all of the buttons on the museum’s information panel without placing the headphones on and then belched. Rolling my eyes once again, I walked away to the other side of the room. I was discouraged because I knew there were many who shared in his lack of empathy.

MANZANAR – SO MUCH MORE THAN AN APPLE ORCHARD

At Manzanar, Spanish for “apple orchard,” many of the original buildings no longer exist. The grounds remain a national historic park service site, preserving the dark and sordid American history. Barbed wire still frames the three-and-a-half-mile driving tour. The wind whips sand and dirt at high speeds under the desert sun, even in the spring. After a two to three-hour tour, I come away with a slight sunburn, dry eyes, chapped lips, and a heavy heart. One can only imagine what the summer and winter must have been like for some 10,000 prisoners over two-plus years.

My tour concluded at the Manzanar Cemetery, where a beautiful obelisk stands tall against the backdrop of the commanding, snow-capped Eastern Sierras and the great Mount Whitney. The three Japanese characters read, “soul consoling tower.” Another plausible translation is “memorial to the dead.” Several graves dot the surrounding rocky grounds, as well as a pet cemetery.

I leave a stone upon the column that has traveled with me for months. It was with me on my travels to Peru, symbolic of protection and guidance. The solemnity was palpable. I earnestly tried imagining walking the grounds of this place, an American prisoner, in early 1942. Under the afternoon sun, I silently hoped our children wouldn’t have to visit a place like this in the future of our generation.

Leave a Reply